- Home

- Lesleyanne Ryan

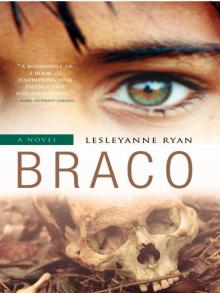

Braco Page 4

Braco Read online

Page 4

“Mike!”

“Goddamnit.”

He rolled his head back into the pillow and pulled up the sides, covering his ears. The thumping stopped and he slipped into sleep.

Burning furniture. Table legs. Armchairs.

Keys jingled.

A click followed.

Mike opened his eyes on a bright window. A moment later, a shadow eclipsed the light and a hand shook his shoulder. Mike’s vision adjusted; Brendan’s stocky frame stood in front of him.

“Get up, Mike.”

“I am up.”

Clothes landed on his head.

“You’re awake. You’re not up. For God’s sake, you said you’d go.”

Mike squinted, wondering what he had said. The last thing he remembered was a soldier leading him into a basement full of black-market alcohol.

“I wouldn’t have wasted my time if I knew you were going to fall off the wagon.”

“Wasn’t my fault,” Mike said, wiping drool from his chin.

Brendan shook his head. His short, flaming red hair mirrored his mood. “What? Does Bosnian beer have legs? Did it walk up to you and force its way down your throat?”

Mike chuckled into the pillow.

“Fine.” He heard zippers. “Where are we going?”

“Srebrenica, you fool. I expected you in the lobby an hour ago. I thought you of all people would jump at this chance.”

Mike rolled onto his back; the room spun. He swallowed bile and looked up. A blurred form stuffed a black bag.

Brendan worked for an American news affiliate, but neither he nor his cameraman spoke Bosnian. In the last month, the pair had lost their translator to the BBC and their driver to a sniper. Mike had offered to do both jobs; it supplemented his income enough to keep him in the country longer than he had anticipated. The agreement also landed him more photos.

“I didn’t think we’d go,” Mike said. “The UN said there would be air strikes today. The zone of death, remember? They won’t let us anywhere near the town.”

“Christ, Mike. Have you been asleep all day?”

Brendan sat down on the edge of the bed and handed him his glasses and a cup of coffee. Mike stuffed a pillow behind his back and sat up, taking a sip. He glanced at Brendan who glared back.

“What?” Mike asked.

“They dropped two bombs and went back to Italy. We’re guessing the Serbs threatened to kill the Dutch they took from the observation posts. The Serbs are probably in the town by now. Last I heard the population was heading for Potocari.”

“Goddamnit,” Mike said. The coffee repeated and he swallowed the acidic sludge. “There’s going to be a lot of body bags.”

“And we need to leave now if we want a front row seat.”

“Fine. Fine. I’ll meet you downstairs.”

Mike dug into his jeans pocket and pulled out his wallet, opening it.

“What the….”

“They drank you dry, didn’t they?”

“Bastards.”

The soldiers he’d met the previous night had told Mike they would take him to meet a man who helped people escape from Sarajevo through a tunnel in the hills. Mike rubbed his forehead and pushed his glasses up.

I should have known better than to accept that first drink.

Brendan dropped the packed bag at the foot of the bed.

“Look. Shit, shower, and shave and get down to the lobby in fifteen minutes. I’ll take care of the bill. Consider it payment for your translating services this week. And next week.”

“I’m still doing your soundman’s work. How about we call it even?”

“Then you’re out of luck. He’s cutting through the red tape in Zagreb. I expect him here in a week or so.” Brendan moved towards the door then hesitated. “On second thought, skip the shit and shower. Just piss and pack.”

He stood at the door, staring at Mike.

“I’m up. I’m up.”

Brendan shook his head and left. Mike swung his legs over the side of the bed, immediately regretting the motion. He dropped his head into his hands to steady the rotating room. The coffee repeated.

After a few deep breaths, he stumbled to the bathroom and turned on the hot water faucet. Cold water sputtered from the tap. He soaked a towel and held it to his face. Feeling half awake, he dressed and then checked his camera bag to make sure the soldiers hadn’t made off with everything else.

Cameras, lenses, film, meter, filters, batteries. Everything present and accounted for.

A metallic noise suddenly shattered the silence of his room. Mike’s knees gave out and he dropped to the floor behind his bed.

Damned garbage containers.

He stood up, walked to the window and looked out over a pile of sandbags. On the street below, teenagers were diving into dumpsters looking for the food they knew the Western journalists wasted without a second thought. Three dogs sniffed the rubble at the base of the containers, roving back and forth like caged wolves.

Then a cat scrambled to the top of a container, startling the teenagers; it took a long leap through a broken window. A dog tried to follow. It yelped as it hit the window sill and dropped.

Another lid crashed down.

Mike shivered.

As much as he hated the noise, he preferred it to the alternative. The hotel routinely assigned journalists to the rooms facing Putnik Street, a wide multi-lane Sarajevo roadway in front of the hotel. On his first trip into the battered capital he learned that the road was visible to Serb snipers.

He closed his eyes, remembering every detail.

The first time he had heard the popping sounds outside his window, he didn’t flinch or duck. He thought a car had backfired. Then he’d looked outside.

Two women lay in the middle of Putnik Street, the contents of their bags strewn around them. One lay still in a puddle of blood. The other cowered behind her friend’s body, shrieking. A French armoured personnel carrier rolled into the middle of the street to protect the women.

Mike had done the one thing he had come to Sarajevo to do: he grabbed his camera and rushed outside to take pictures. The next day, the same thing happened. A repeat on the third day had bewildered him and he’d buttonholed a British officer in the hotel lobby.

“Why are there no sea containers there to protect them? You’ve got them on the road behind the hotel. Why not here?”

“They won’t let us,” the officer had replied, glancing around.

“What do you mean they won’t let you? Who?”

“The city government.” The officer had turned and pointed to the crowd of reporters huddled near the hotel entrance. They looked like they expected Tom Hanks to walk by at any moment. “This is what the Bosnians want. A sniper victim falling dead in front of the media. This way, they make sure the world doesn’t forget what is going on here.”

Mike had turned away from the peacekeeper in disgust and walked over to the front desk to request a room change. When he sent out the photos he’d taken the day before, he included a commentary on the politics behind the killings. They’d published the picture but cut the “unsubstantiated” story.

“Ready?”

Mike opened his eyes. Brendan’s new cameraman, Robert, stood in the doorway. He carried a video camera on his shoulder, which looked too big for his slight frame.

“Brendan said to tell you the escort leaves with or without us in ten minutes.”

Mike tossed the towel on the dresser.

“I’m coming.”

Robert didn’t move. “He told me to help you.”

“No, he told you to make sure I was up and moving.” Mike picked up the black bag and tossed it at Robert’s feet. “Go on. I’ll be right down.”

Robert picked up the bag and wa

lked away. Mike turned to the dresser and shuffled through some papers. He picked up a laminated black and white clipping that showed an emaciated boy wearing only a pair of shorts.

The caption read, “Starvation in the heart of Europe. Twelve year old Atif Stavic weighs only 63 pounds. Food drops and convoys are doing little to alleviate the hunger. Should the UN intervene?”

Mike had never returned to Srebrenica to tell the boy his face was known worldwide; at least it had been for a few days. His photos and the footage from other journalists had sparked outrage over the Serb blockades. Within months, the UN designated Srebrenica and a fifty-square-kilometre area around the town as the first United Nations Safe Area. Only the Canadians responded to the UN request for troops, sending in one hundred and fifty peacekeepers when ten thousand were needed. Eight hundred Dutch replaced them a year later.

Mike liked to think the photo had made a difference. The truth usually did.

“Where are you now, Braco?”

He dropped the picture into his knapsack, checked the room over, and left.

TUESDAY: ATIF STAVIC

ATIF STARED AT the blood-red disk setting through a pillar of smoke. The air had started to chill and he rubbed his arms, his gaze moving to the field of corn behind the factories in Potocari. People wandered through the stalks, stripping the plants bare. Others swarmed the houses sitting on the edge of the field, looting anything they could eat or sell. Artillery echoed in the hills, too distant to be a threat. The steep hills and deep valleys could make the sound carry a very long way.

Or conceal it altogether.

Atif turned away and took a step closer to the water spigot. The woman next in line didn’t have a container. She cupped her hands under the water, gulped down mouthfuls, and then gave water to her little boy to drink. Afterwards, she dunked his head under the water and soaked a towel. Someone tapped on Atif’s shoulder. He turned; a young woman held up a paper bag.

“I need a container,” she said.

She opened the bag to reveal a large chunk of red meat. Atif stared at enough calories to feed his family for two days.

“I can’t,” he said, his mouth watering. “I’m getting water for six people.”

The woman frowned and walked on without a word. She moved along the line until an old man gave up a small bottle for the beef.

How would he cook it?

A woman behind Atif grumbled. He turned back to find the spigot free. Sliding his container under the stream, he waited until it overflowed and then capped it. When he picked it up, he was surprised at his strength after so many days in hospital. He couldn’t remember if he had eaten.

Mama must have made me eat something.

Getting food over the last few months had not been as difficult as he expected. The Bosnian army had rejected his application, telling Atif he was too young to join and that, without a weapon, he would be useless to them anyway. Instead, they hired him as a courier and Atif had spent the spring and summer carrying messages, food, and ammunition to the trenches closest to town. They paid him with cigarettes and Deutsche Marks and enough food to ensure he would have the strength to make the runs every day. Now he had the strength to take care of his family.

“You’re a man now, Atif,” his father had told him on a late summer day three years before. “While I’m gone, it’s up to you to take care of them. Can you do that?”

Atif had stood tall before his father and accepted the responsibility. Three months into the war, they were still in the woods, their food supply dwindling. Any hope the war would be short had vanished. His father said they had to do something before the winter set in. He decided to chance a walk into town to get news and to see if he could find someone to smuggle them to Srebrenica or Tuzla.

Atif remained standing next to his mother as his father walked into the darkness. His father returned before dawn. Atif had hidden his shame; he had done nothing except sleep.

“They slept in peace, Atif. You did a good job.”

Six days later, they were in the back of a VW heading for Srebrenica.

So long ago.

Atif dragged the water container through the ocean of refugees, their hands and feet lapping at him like waves against a boat. He stopped to rest and looked around. Dutch peacekeepers were handing out towels and bottles of water. People pleaded for food.

“Soon,” the peacekeepers replied to every inquiry.

Atif studied every peacekeeper he saw but none were familiar. Some of the people in the line-up had told them the Dutch were evacuating their remote observation posts. One person said that some of the Dutch had been taken hostage. From the southern posts, another had added. Jac had been sent to a post called Romeo near Jaglici in the north. Atif wondered if he was still there or back in Potocari.

He dragged the container towards the bus depot where the peacekeepers had set up a medical tent. People lined up for help. Dutch medics spoke to them through translators. Atif pulled the container through the line of people and made his way to the side of the wrecked bus. His mother was tucking a blanket under Tihana’s head as his sister slept in Lejla’s lap. Ina came to his side and helped him the last few steps. They laid the container down next to Adila and his mother stood, giving him a quick hug and kiss.

“I was beginning to worry,” she said, “but someone said the line was long. Did you have any problems?”

“No, Mama.”

Atif stepped over his sleeping sister and sat next to his mother, surprised to find a pot sitting on top of a small camp stove next to Ina.

“We borrowed it.” She pointed to the far end of the bus where an older man sat with his wife and daughter. “I promised them all the water left in the pot and half dozen boiled potatoes.”

Atif helped his mother pour the water and light the stove. They dropped twelve potatoes into the pot and waited for them to boil. Hungry eyes in the crowd watched their every move.

“Maybe we should boil them all,” Atif said.

His mother followed his gaze.

“We don’t know how long we’re going to be here,” she whispered. “We don’t know if the Dutch have any food to give out and we don’t know how long before they can get the trucks here to get us out. We could be here for days.”

“Don’t worry about them, Atif,” Ina said. “There’s plenty of water. People can last a long time without food as long as they have water.”

Atif ate the half-cooked potato with his back to the crowd.

His mother returned the pot to the family with six potatoes in the water. Lejla woke Tihana; she ate only after Lejla pretended to feed the toy soldier. Atif’s mother peeled the skin from her own potato and gave it to Tihana. She pulled one of the water bottles from Atif’s pack and then dug into her own pack, taking out a small plastic bag containing the last of their salt supply.

Salt had been a rare commodity in Srebrenica. The humanitarian convoys seldom brought salt into the town; the residents had to buy what they could off the black market. The peacekeepers told Atif the Serbs usually stripped the convoys of salt destined for the town. Atif didn’t understand why until Ina told him the lack of natural iodine in the area meant an increase in the risk for diseases like goiter. Some people found clumps of road salt and boiled it to use in place of table salt, but Ina said they were wasting their time. Road salt contained no iodine.

As time went on, it became harder to find salt, even on the black market. Atif had lucked into the small bag one day when he’d brought up the army’s supplies. He’d traded a soldier three cigarettes for the bag of salt and considered it a steal.

His mother took several pinches, mixed it with the water, and passed it around. When they finished, Atif offered to refill the containers.

“We should wait till morning,” his mother said. “It’ll be dark soon.”

“That’s okay

,” Atif replied. “I know the way. And there won’t be as many people there this time.”

His mother glanced at Ina.

“Perhaps he should,” Ina said. “It’s better than facing the crowds in the morning when it’s hot.”

“Okay,” his mother said. “But don’t go near any of the rivers. We don’t know where the mines are around here.”

Atif kissed her and then emptied the water from the large container into the smaller ones. He left the bus and made his way through the crowd. A woman tried to calm a screeching infant. Two women held each other, crying. Another woman held her young daughter’s hand as the girl urinated next to their spot. An older woman vomited. Two peacekeepers carried a woman in labour to the medical tent. A blanket was held up, offered in exchange for food. Atif said no and kept walking.

He stopped and stared at a boy. The blond hair and pale blue shirt were familiar. Atif walked towards the boy and then hesitated. He closed his eyes tight and saw Dani’s face, the little boy’s eyes staring at him from behind the car.

A flash, brilliant white.

Darkness.

Atif opened his eyes.

“It can’t be,” he whispered to himself. He stepped forward and looked down.

“Dani?”

The boy turned and looked up.

“Who?”

Atif turned away. Ahead of him another blond boy sat with his back to him. He blinked, but the boy remained. Atif walked towards the boy and touched him on the shoulder. A stranger’s eyes peered up.

“Sorry,” Atif said

He turned away, took two steps, and then reached out to steady himself against a tree. His head spun as he lowered himself to the ground. He squeezed his eyes shut, rocking back and forth.

It’s not happening, he told himself. Just tricks. The mind plays tricks. Remember? The soldiers used to say that.

Someone touched his shoulder. Atif flinched.

“Are you okay?” the woman sitting next to him asked. She was rocking a baby in her arms.

“Yes,” Atif replied. He pointed to the bandage on his temple. “I just have a headache.”

Braco

Braco